Mark Whiting and Kiersten GarciaThanks to one of the largest magnetic resonance imaging machines in existence, researchers at Stephens Family Clinical Research Institute and the Carle Illinois College of Medicine are building knowledge in hopes of providing more answers for people managing traumatic brain injury.

Mark Whiting and Kiersten GarciaThanks to one of the largest magnetic resonance imaging machines in existence, researchers at Stephens Family Clinical Research Institute and the Carle Illinois College of Medicine are building knowledge in hopes of providing more answers for people managing traumatic brain injury.

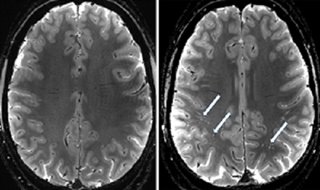

The work centers on views of the glymphatic system in the brain – submillimeter in size – that surrounds vessels in the brain and helps the brain clear out metabolic waste from ordinary living. Injury to the brain, and particularly repeated injury, causes disruptions to this area that can lead to impaired sleep, mood disorders, migraines, stroke or Alzheimer’s disease.

“Impaired glymphatic function may be a common denominator in all neurological conditions,” Mark Whiting, PhD, and clinical investigator in neurosciences at Carle Foundation Hospital said. Whiting is leading the TBI Research Group and working alongside Kiersten Garcia, PhD, staff scientist, Stephens Family Clinical Research Institute, Carle Foundation Hospital.

They partner with Carle Illinois College of Medicine students Daniel Ng, Grace Brolly, and Maria Bederson and all are presenting on their traumatic brain injury findings in June at the National Neurotrauma Society Conference in Austin, TX.

“The collaborative nature of this research and use of the powerful MRI helps drive us forward with discoveries that can lead to new treatment approaches for brain injury,” Garcia said.

Whiting likens what happens after brain injury to a garbage truck that overflows with trash. Damage to the glymphatic system causes metabolic waste to back up, and clumps of waste eventually accumulate in the brain tissue itself. Repeated head injury seems to dramatically alter the function of the waste removal system, and the hope is to more accurately classify this type of brain injury, he said.

Whiting likens what happens after brain injury to a garbage truck that overflows with trash. Damage to the glymphatic system causes metabolic waste to back up, and clumps of waste eventually accumulate in the brain tissue itself. Repeated head injury seems to dramatically alter the function of the waste removal system, and the hope is to more accurately classify this type of brain injury, he said.

For the research study, patients with head injuries who enter the Emergency Department at Carle Foundation Hospital may participate in the study and have brain scans three times – within 72 hours, at one month and at three months – using the 7 Tesla MRI scanner. The 37,000-pound scanner in use at Carle since 2020 is one of the first in the country and the only such scanner in the state of Illinois used both for research and clinical evaluations.

The powerful scanner housed at the hospital resulted from a partnership between Carle and the University of Illinois in collaboration with the university’s Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology and the Stephens Family Clinical Research Institute, Carle’s research enterprise dedicated to supporting new discoveries addressing critical healthcare challenges.

“The 7T is helping us uncover novel information about so-called mild traumatic brain injuries,” Whiting said. “Typically, a patient with a head injury arrives at the Emergency Department and receives a CT scan which shows if there is any bleeding in the brain, but the 7T shows even more detail,” he said.

Most glymphatic research is conducted on animals but there continues to be a movement toward more accurately classifying brain injuries in humans, Whiting said. “One of the hopes is people will realize mild traumatic brain injury is a misnomer. Yes, they are mild compared to life-threatening brain injuries. But there are structural changes occurring in the brain after these mild injuries, and this can’t be seen with conventional imaging techniques.”

By building a registry of patients who experienced traumatic brain injury, the team can track individuals over time and see the changes in the brain from its early stages. “One of the most surprising findings is how quickly we are seeing changes in the brain after a head injury. The perivascular spaces that make up the glymphatic system enlarge rapidly, sometimes within hours of injury. This may help the brain eliminate harmful waste products. But in people who have experienced multiple head injuries, this response seems to be diminished.”

Ultimately, the research will help us understand why evident damage to the glymphatic system in the brain happens in some individuals and not others, Whiting said.